The weather and my schedule finally converged this week to spend time with Abner Stone’s gravestone. And possibly some time with Abner, himself. I’ll get to that in. future post. The marker is made of porous red sandstone, a popular material in colonial Massachusetts and Connecticut burial grounds, so I took care not to scrub too hard. Below are the materials I used for the initial cleaning, meant to remove any lichen, surface dirt, and other buildup from nearly three centuries of being outdoors:

rubber gloves

apron

filtered water

water can

soft bristle brush, preferably natural

wood chopsticks

rubber spatula or scraper

Woolly Wash soap flakes

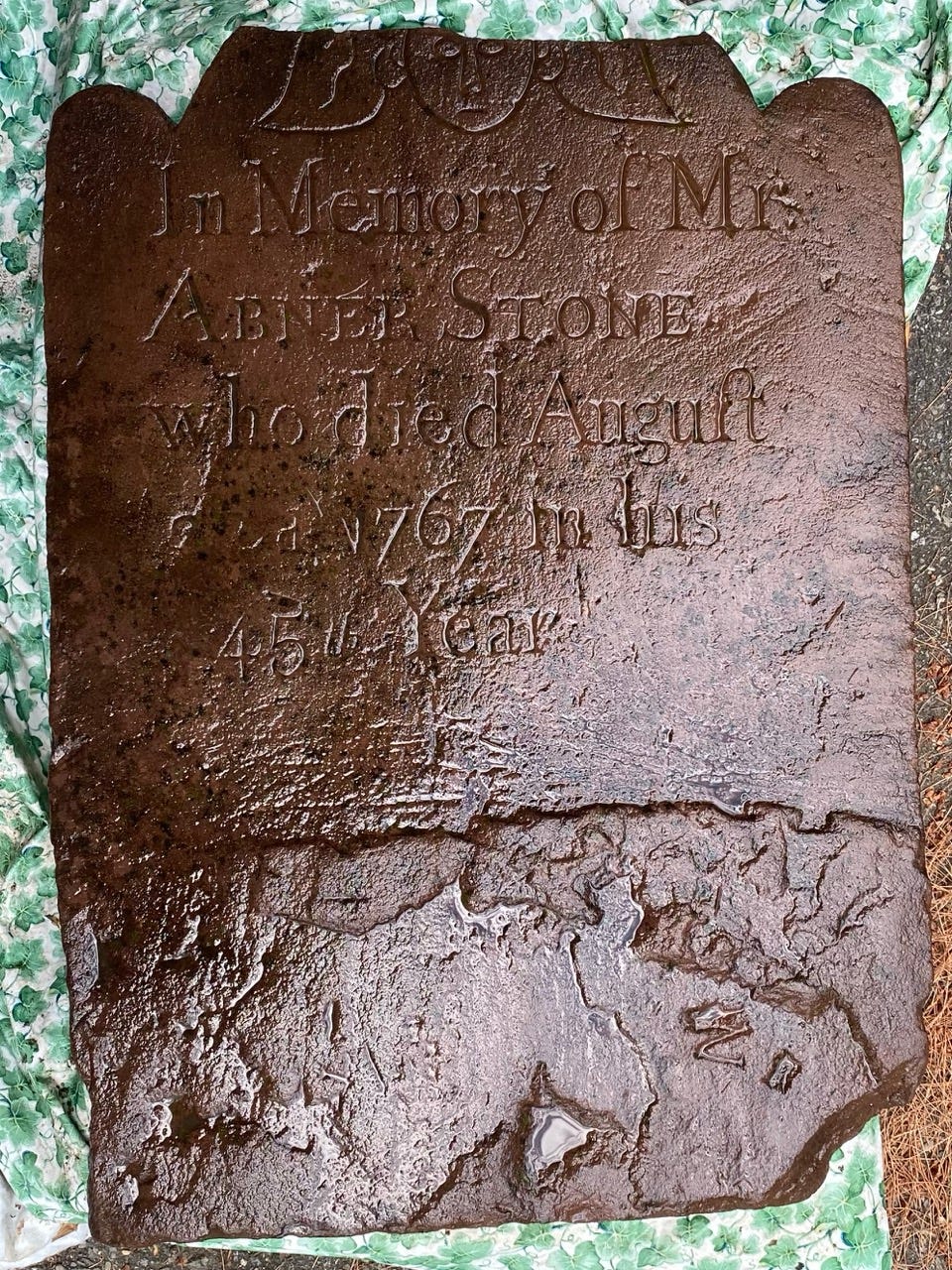

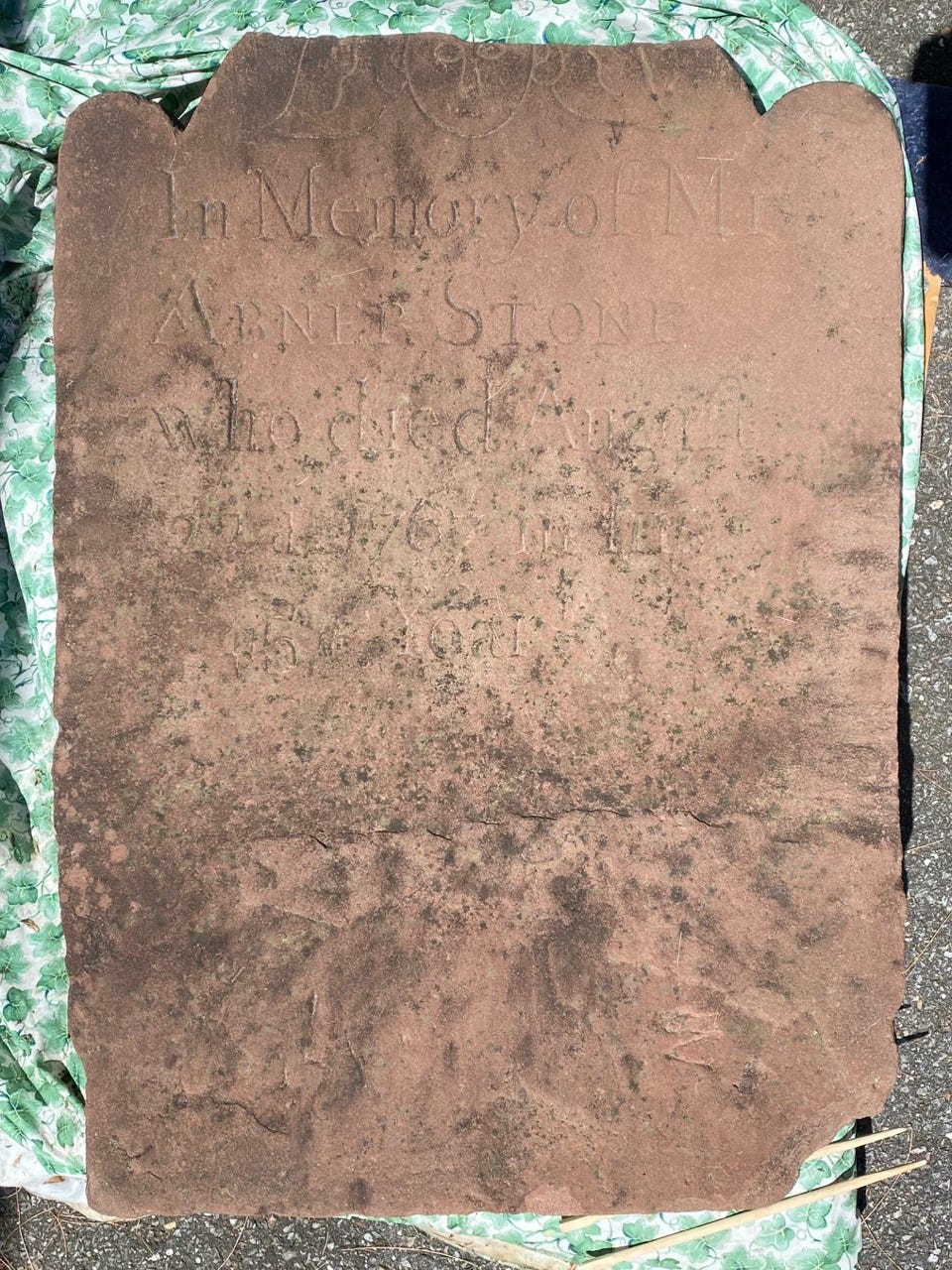

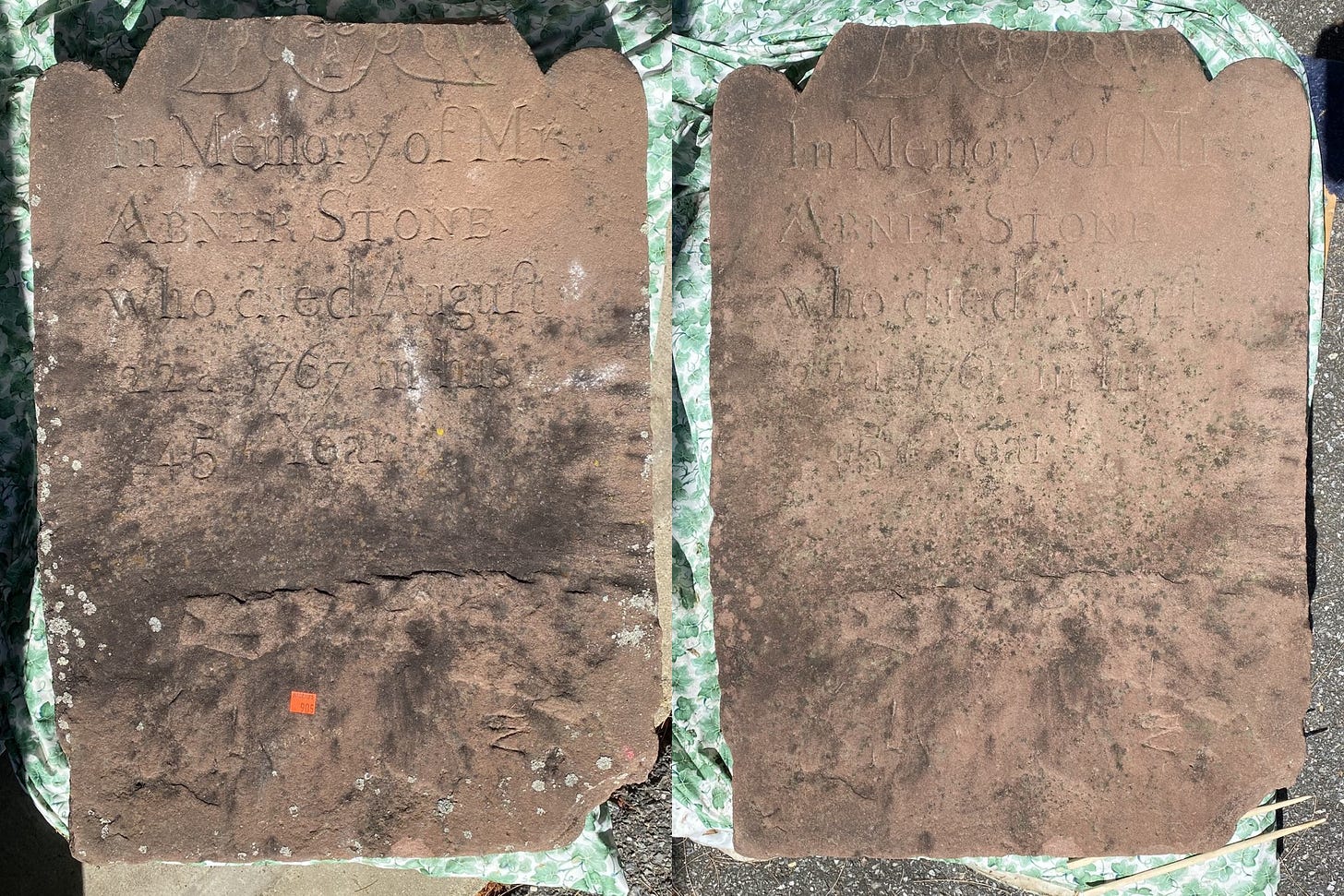

Cleaning historical artifacts is always nerve-wracking, especially when one is not a professional. There’s no worse feeling than being the person to wreck an object by trying to make it better. At least I assume so, as most of my personal experience has come from watching professionals correct previous mistakes. Grateful that it’s not made of slate. I’m on Day Four of Six being away from my desk on business, so it will be about a week before the next attempt a cleaning. Meanwhile, the stone revealed a few clues to its origins upon closer inspection.

One of the helpful tips I learned from the lovely gravestone cleaners of the Internet was to keep the stone as wet as possible during the whole process. I don’t have a pressure cleaner, so I borrowed my grandmother’s water can that she uses to water her small jungle of house plants. Filtered water is very important because public or even well water can contain minerals that might harm the stone. If you don’t have a filter, gallons at the grocery store are usually inexpensive. After wetting the stone, I used a natural bristle brush to gently clean the stone in slow circular movements.

Gloves are essential for this work because I’m vain and didn’t want to make my manicure, already on its last legs, any worse. They’re also protective to you and the stone. By the end of the first wash, the pool of tarp water was a dark brown. Yuck. When the stone was still wet, I worked away at the moss and lichen with chopsticks and the same tool my mother uses to remove stubborn dough from her wood cutting board. Does anyone remember Pampered Chef parties? Their pan scrapers are just hard enough to not bend, and they have rounded edges for delicate removal.

During the second cleaning, I added a few soap flakes as some dirt would just not come off. Don’t panic: Woolly Wash is extremely delicate and made of all-natural materials. Yet even with two wash and rinses, some dark green moss and dark spots remained. The stone is now “resting” before I can try again, possibly with water and baking soda. All work like this requires some testing, and I’ll only apply a small amount to the stone’s lower side for a test when it’s completely dry. The marker only looks darker in some remaining moist spots after towel drying.

There are two intriguing details of this gravestone. The stone’s lack of decorated columns on either side of the text is unusual. Not all gravestones in this culture were elaborately detailed, it’s just odd that Mr. Stone would buy one with specific space for such carvings. There’s also a possible carver’s mark on the marker’s lower half that would have been buried. It could be a pointy “E,” a sideways “M” or “W.” Let me know what you think it may be in the comments, and please drop a like and/or subscribe if you enjoyed this post. It helps other readers find my work and the dopamine hit is pleasant, too.

Thanks for describing the cleaning process. I’m fascinated to read what you discover about Abner Stone.