The first time I heard about Leonora Carrington was from Pam Grossman, host of The Witch Wave podcast, a super fan who regularly references the artist and her oeuvre on the show. Although I recognized all the male artists’ names surrounding hers during a quick search, Carrington’s hadn’t come up in my 20th century art history education. There are many reasons for this, however that lack did grant me the privilege of seeing Carrington’s work in person during her first New England solo show.

Leonora Carrington: Dream Weaver opened on January 22 at the Rose Art Museum, part of Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass. It was another “first” for me, as I’d passed the Rose dozens of times on the commuter rail but never visited. The space was bright, clean, and full of people, more than what was expected. Their numbers were no doubt boosted by a review in the Boston Globe that day and, as my mother reported via text message, radio advertisements.

The exhibition presents quality over quantity; it’s not a retrospective, yet displays diverse examples of Carrington’s work in multiple mediums throughout her life. For each of her complete, large scale paintings, there was at least one accompanying study for the finished piece. The majority of these were from private collections and rarely on public view, if at all.

With Surrealist art I trust my first feeling upon viewing an object, usually “ooh!” or “ugh,” but rarely “eh.” Surrealist art often contains so much dream imagery that it can’t be anything but subjective, both in its creation and its reception. I’ll leave the critical analysis to those who want to chew on that, and instead focus on the paintings that struck me most as a Carrington novice. For those totally outside the field, look at the art that draws you in first, for whatever reason. That’s where the discovery happens.

Three of my favorite Carringtons contained, no surprises; imagery of hands, birds, and eggs. The latter is “a ubiquitous symbol of birth and transformation, central in myriad cultures and occult beliefs,” according to the description panel for The Chair: Daghda Tuatha de Dananan. Depicting the Irish sun god Daghda as an elaborately painted, high-backed chair, it oversees a white rose emerging from a large egg on the table. From below, a pair of disembodied hands hover over a smaller egg, seemingly creating the force that spurs this growth. Do these hands belong to Danu, the universal Mother goddess, “[playing] with the yet unrevealed future?”

For Nunscape at Manzanillo, Carrington exercised the ultimate Surrealist right of not explaining her imagery. “My art is wiser than I am,” was all she’d reveal. Perhaps that descriptor was a nod to the prominent white owl creature, sitting atop a carved plinth on yet another egg, sporting three eyes and possibly crunching on another bird. If that’s the standard of “wisdom” in this painting, are the scattered nuns running from this beastly bird or toward it? Where does intelligence go when there’s no direction for its education? The black egg nestled under the “owl” foretells a bleak future, but nothing is certain until it cracks.

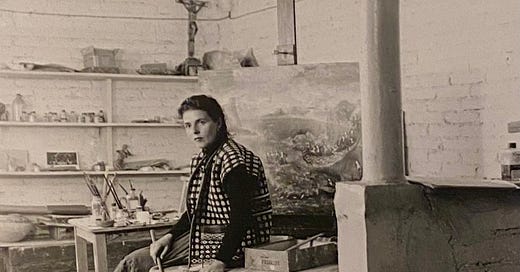

One of the more realism-leaning paintings in the exhibition was The Last Resort, an oblong image of what looks like a Gambel’s quail standing tentatively on steps of a green painted door. Upon closer inspection, the door is surrounded with four scorpions, a figural sunflower sconce, and an angelic figure hovering over the door’s corner. The door was identified by Carrington scholar Salomon Grimberg as belonging to the Hungarian-born photographer Kati Horna, who took the studio shots of her above. As family birds that travel together, quails often symbolize community and protection, such as this male is seeking. Would you let him in? I would.

Also on view at the Rose until June 1 is Hugh Hayden: Home Work, another New England solo premiere for the American artist (b. 1983). Hayden’s multimedia sculptures present a survey of his work for the past decade that combine natural and unnatural materials. As an African American artist, his subjects evoke a discomfort with the “American Dream,” how that immaterial ethos does not manifest in reality for most. In Scarecrow, the bark Hayden applied by hand to a Burberry trench shows how many use clothing as status objects for protection against the society that reveres them. Its stand is carved from the finest African hardwood, Gabon ebony, a highly valuable yet subtle material. And yes, that finial is absolutely a penis.

One more personal discovery was in Surrealism(s) – Then & Now, a selection of works from the Rose’s permanent collection curated to celebrate a century of Surrealism. Pierre Roy (1880-1950) was a latecomer to the Surrealist movement, about twenty years older than most of its founders but converted from Fauvism by the work of Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978). More of a still life at first glance, For Madame is a shrine to love, composed with objects from his own collection. Each had a personal significance for the artist, and many made multiple appearances in his altar-like paintings. Again, my taste is predictable, you all know I love an arrangement.

The Rose also owns a permanent Mark Dion installation, The Undisciplined Collector, a recreation of a 1961 collector’s den with rotating art from the museum’s collection. This is best viewed when there aren’t gangs of art students squeezing themselves into it, yet that’s part of the experience, isn’t it? Special thanks to Dorian Keeffe, collections care and exhibition production assistant at the Rose Art Museum, an old friend from the art world trenches, and a terribly talented Surrealist in his own right, for the invitation.

Thank you highlighting this fascinating artist. I miss living somewhere with a thriving museum and cultural scene.

The Rose doesn’t yet have the catalog available on their website. 🙁